Public concerns lead to options for sewer rate changes

Outraged residents took to social media this summer, over concerns that they were being charged for sewer services they weren’t using. Because the residents were using water for their lawns and gardens, and therefore weren’t putting it into the sewer system through waste pipes in their homes, they felt that being charged for the same amount of sewage production as water consumption was unjust.

Councillor Trevor Bolin brought the matter up at the July 24th council meeting, with a motion requesting that staff review options for billing sewer rates to take seasonal watering into account. Generally, water usage in the summer months, May to August, is ten per cent higher than in winter.

Since bringing in the water meters in 2007, the billing process has undergone several changes, ending up with the current full-cost recovery model, which was adopted in 2012. This means that no taxes are collected to pay for the water and sewer infrastructure. Instead, it’s self-sustaining, by having the bulk of the revenue going into the reserves. This supports operational costs, major project costs, replacement, and new infrastructure costs. For example, the water and sewer infrastructure in the 100 Street project is paid for out of the reserve.

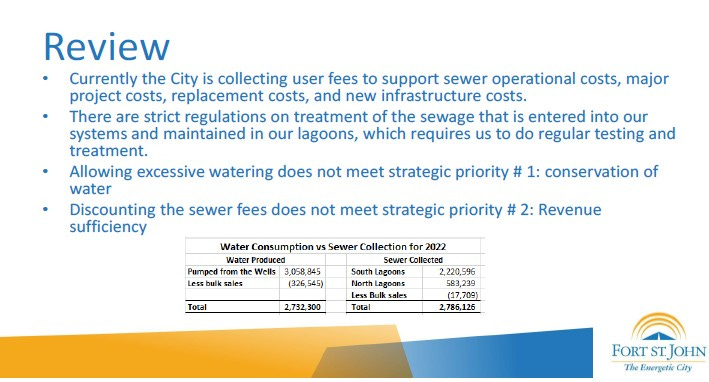

From 2008, the city’s main objectives with respect to the rate structure were based on two priorities. Priority #1, conservation of water; and Priority #2, revenue sufficiency.

Allowing excess watering doesn’t meet Priority 1, and discounting sewer fees doesn’t meet Priority 2, according to Shirley Collington, City of Fort St. John’s Director of Finance.

Collington studied the last three years of water and sewage usage and found that the numbers were very close. She said that this is due to incorrectly installed weeping tiles and sump pumps. When residents water their grass, the water is being collected by the weeping tiles and going into the sewer system.

Adjustments to billing could be made, but Collington sees some problems with each option.

“Water and sewer have to stand on their own two legs, and the rates formula reflects this,” she said. By being standalone functions, the city doesn’t need to borrow money when work needs to be done.

“We have a sewage reserve of $12 million, but we’ve spent $10 million of that on infrastructure.”

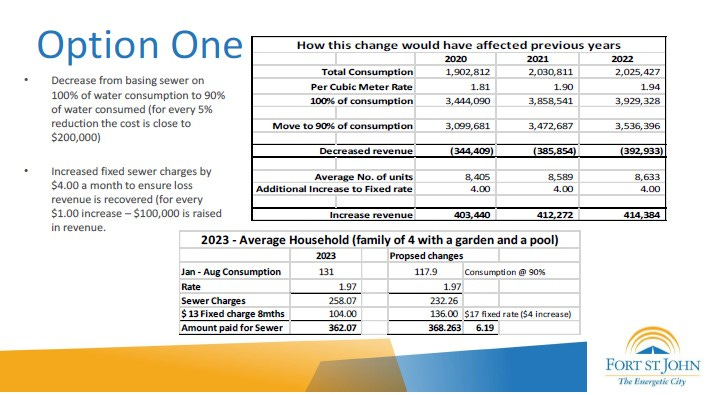

Option 1 involves incorporating a discounted rate for the summer months of May to August and adding $1 to the fixed rate.

“We could increase the fixed rate, so then we’re guaranteed to get that extra dollar per account. Then it doesn’t matter what the consumption is, at least we’re getting the revenue,” Collington said.

The downside is, “by giving them a discounted rate, they will think they can use more water, which doesn’t meet the conservation priority,” she said. “Do we want green lawns or are they okay with the brown?”

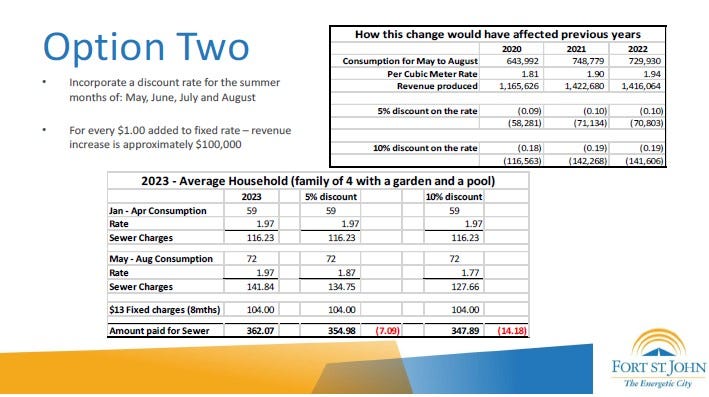

Option 2 looks only at the high usage months, by giving a discount in those months. This option doesn’t make a lot of difference to the charges on the accounts, Collington explained, but would create more work for staff and potential for errors.

The third option is to leave billing as is.

“I don’t think it’s the $14 that bothers people,” said Bolin. “I think it’s the fact that they’re watering, and it goes off their grass, into the road.”

“If we were truly listening to what our residents’ concerns were, it would be Option 2 with a ten per cent discount,” he said.

The city’s Chief Financial Officer, David Joy said that one way or another, the city still needs to add to its reserves.

“The perception is that they pay less on the variable, but the city’s going to gain on the fixed rate,” Joy said.

Bolin disagreed. “The way I look at it is, the fixed rate is what our capital reserve should be. The amount we’re charging monthly on their bill should be for what they’re using.”

“To tie those two together defeats the purpose of what we’re trying to do with this recommendation,” Bolin said.

Councillor Gord Klassen said he much prefers green lawns to ones with only dandelions and noxious weeds that can grow without water.

“When we look at the community as a whole, we’re trying to build a beautiful community that people want to live in and come to. That’s a pretty big deal,” Klassen said. “I don’t think we should shortchange that use of water.”