Council committee suggests co-op housing as partial solution to homelessness

Since September 2024, council’s three-person Council’s Response Committee on Housing and Emergency Shelter (CRCHES) has been working to assess the challenges of housing insecurity in the community and find a solution.

Councillors Trevor Bolin, Sarah MacDougall and Gordon Klassen spoke of the progress they’ve made and ideas they’ve come up with to alleviate the homeless situation in Fort St. John, when they presented their report to the rest of council on February 24.

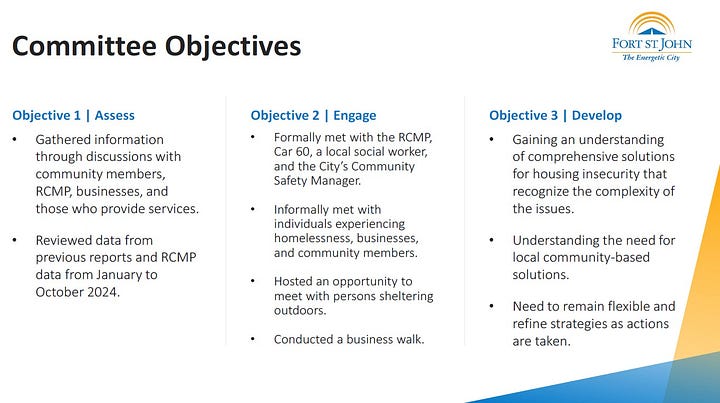

CRCHES objectives were to assess, by gathering information; engage by talking to those experiencing homelessness and people who provide services; develop strategies through understanding the complexity of the issues and the need for community-based solutions; raise awareness through sharing the knowledge gained; and foster partnerships through regular communication with interested parties, such as RCMP, social service providers and business owners.

To meet these objectives, the committee sat down with community partners, including the RCMP, Car 60, a social worker; toured the homeless encampment in the fall, hosted an event where people sheltering outdoors could meet with the committee; and conducted a business walk.

“We really delved into engaging with our community partners as well as city staff who know what’s going on in the community,” said MacDougall.

“We also wanted to go to the residents themselves who are experiencing homelessness, . . . and had some conversations just to hear a little bit about their experience, what’s it like in our community, how did you get to where you are today.”

What they discovered was that contrary to public perceptions, not everyone who is experiencing homelessness is addicted to substances, nor have they been brought in from other communities.

“Sometimes folks think that it’s simply that they became drug addicted, lost their homes and are on the streets. But there are just so many different reasons and pathways to get to that experience of a homeless situation. So, we really want to raise awareness in our community that this is something that really anyone can make a few bad decisions or have some bad things happen to them, and get into the same situation,” MacDougall said.

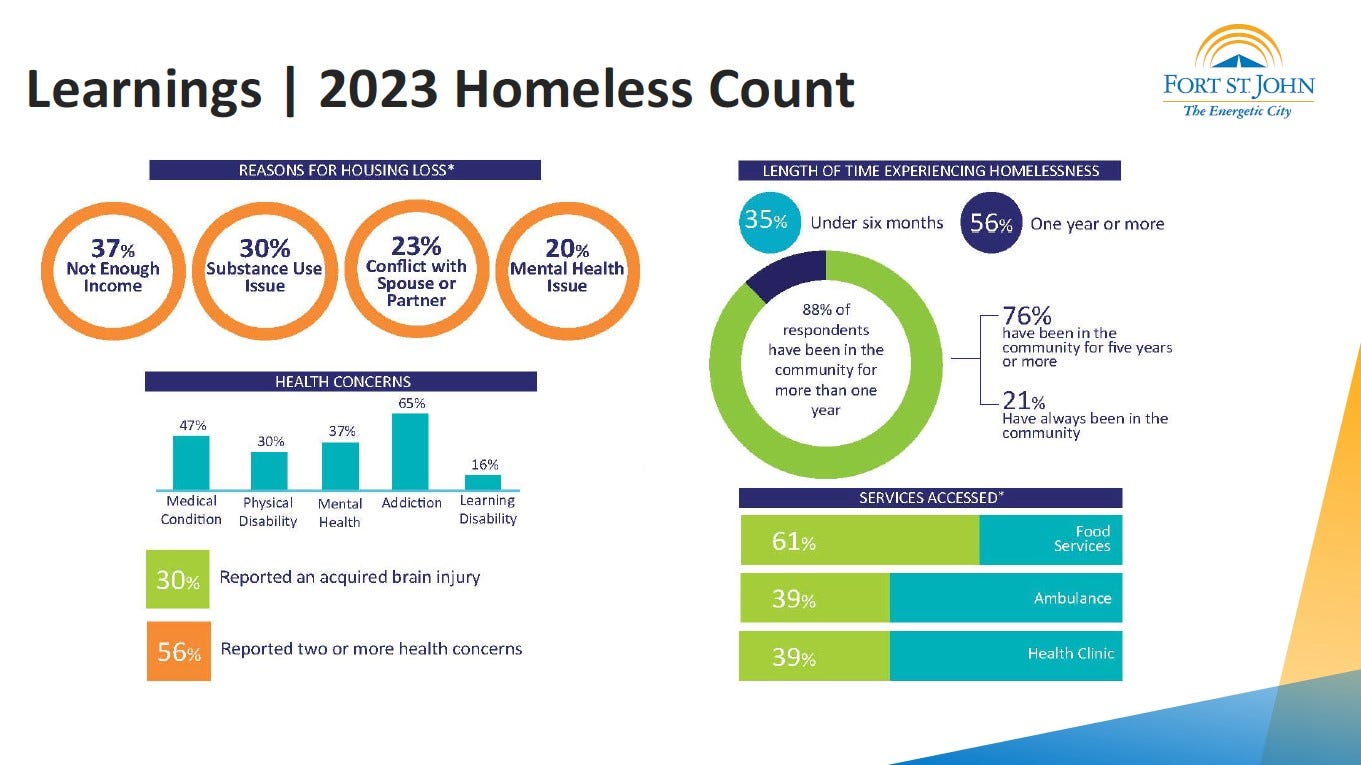

A homeless count, conducted in 2023, showed that there were 102 people who identified as experiencing homelessness, with 40 of those people living outside or in makeshift shelters. Of those 102 people, just 12 percent had been in the community for less than a year.

Substance users make up approximately 30 percent of those experiencing homelessness, which Bolin says, “is contradictory to what people believe on Facebook.”

“If you take in the mental health issues, the personal issues, the income issues, the economy issues, the least amount for reasons for housing loss is substance abuse, which is something that is worth sharing in our community,” Bolin said.

“When you break this down, this could happen to anybody. I think it’s time that we educate the community to think of this issue with more compassion, more kindness and more heart.”

Another contributing factor is the real estate component.

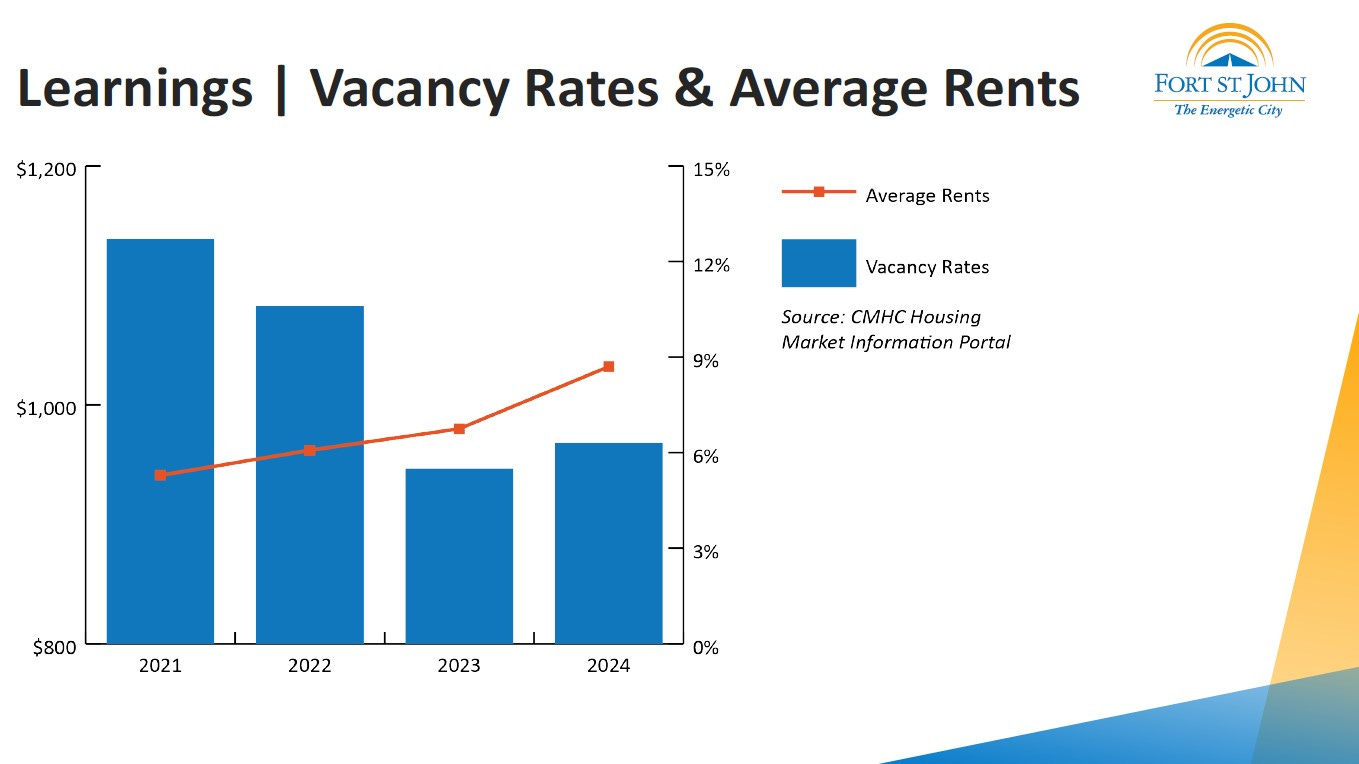

In 2023 when the community noticed an increase in homelessness, the city’s vacancy rate dropped from 12.7 percent in 2019 to 6.3 percent in 2024, accompanied by increased rents. The vacancies that are available, are not affordable for many, especially those on a fixed income.

“We’re at a critical juncture right now,” said Bolin, “because our vacancy rates are dropping, our rents are going to steeply increase as that drops and we’re going to see a possibility of more unhoused individuals in our community,”.

“The bottom line is for us, that we really discovered and confirmed that it’s not simply a housing issue, there is so much more to that it’s very complex. Whether it’s mental health or addictions or just unemployment or some of those other barriers to getting a rental, the affordability of housing the availability of housing – there’s just a lot of different reasons why people are unhoused,” said Klassen.

“We really had that confirmed as we went through and spoke with people and spoke with different agencies that are dealing with these people and just helping us to understand what some of the critical issues are.”

While the committee determined that addressing the housing situation alone wouldn’t be enough, it still recommended to council that:

“Council authorizes CRCHES to meet with the Minister of Housing and Municipal Affairs, the Minister of Public Safety and Solicitor General, and the Minister of Health to discuss potential solutions, including a Co-op Housing Pilot Program in Fort St. John.”

Klassen said that the committee concluded that “a co-op housing scenario would work really well in a community like ours. There’s an availability that is there for people, but there’s also enough of a structure that it would help people.”

“Providing housing without some structure to the individual’s life, really doesn’t result in long-term solutions,” Klassen said.

He added that there is potential for this type of housing in Fort St. John, and that CRCHES has ideas for several funding options to make a co-op housing project possible, including a percentage of the property transfer tax, a percentage of the liquor and cannabis tax, and casino revenues.

Co-op housing models are not unheard of in Fort St. John. The Huntington Place Cooperative Housing was built in 1980 to provide affordable housing for families who were “not necessarily associated with the oilfield,” according to the Co-op’s website.

Huntington Place Cooperative is a non-profit organization built on cooperative principles, and its goal is to provide secure, long-term housing to its members. Even now, 45 years later, Huntington Place is still able to provide affordable living in the community.

Klassen said that council could work with its connections to provincial government, the North Central Local Government Association and the Union of BC Municipalities, to advocate for funding to make co-op housing available in rural communities like Fort St. John.

Bolin explained that the theory on the co-op model is that “there needs to be continuous support, there needs to be a bit of a hands-off, while you have a hands-on approach.”

The theory behind the Housing First model, which was something the city began looking into last year, is that if you have somewhere to call home, you have somewhere to build on.

“You cannot expect someone to change their behaviours or change their situation or scenario when they’ve got this 200-pound cloud hanging over them in the fact that they’ll never, ever have a home to live in.”

The committee believes, after looking at the things other communities have tried, to resolve similar situations, that co-op housing is the best option.

Other municipalities such as Grande Prairie and Prince George have purchased motels to try to provide housing, but Bolin says people in those communities feel that was probably not the best approach.

Medicine Hat did a Housing First project, and it worked for about six years, but “they backed off the pedal a little bit when things got good, and then things unfortunately dropped again,” he said.

Among the lessons the committee has learned, is what they start, they have to finish. The situation won’t be rectified overnight or in a couple of months. That’s why Bolin says he keeps referring to this as a “live document”.

“This is going to change, it’s going to be seasonal, it’s going to be economically impacted, even buildings.”

“Two years from now it could be a matter of a whole different situation and scenario, but once we’ve got our base line, I think from this base, we’re able to branch out, we’re able to add to it, we’re able to continue to grow with it and I think that’s the most important.”